Feel free to leave kind words.

The simple invitation is written in black

marker across the top of white canvas boards nailed to a wooden

telephone pole on the northwest corner of James Street South and

Charlton Avenue.

A faded green alien dangles nearby on a

rusty key chain. There are ribbons; bunches of artificial flowers;

photos of a little girl.

This is not the place where Daniel

Abdolalian-Dolmer, 20, took his last breath — he died in hospital after

being struck by a car while he was riding his longboard down James

Street South on May 7, 2011 — but this is where his loved ones, from

time to time, come to remember him.

“I think the accident scene is always an

unanswered question. How did it happen and why did it happen?” says

Morteza Abdolalian, Daniel’s father.

At last count, the city’s road operations

department knew of 29 makeshift memorials scattered throughout Hamilton.

There is no formal policy for dealing with them, although roadside

crews often inspect them to make sure they’re not a hazard when they

spot one while on routine road patrols.

Bryan Shynal, the city’s director of

operations, says staff have noticed more memorials in the last decade

and will look into whether the city should implement a policy on them

when they review the streets bylaw in the coming year. Other

jurisdictions already have policies in place, including outright bans

that label memorials as distractions for drivers.

Hamilton’s memorials are as varied as the incidents that prompted them.

There’s the one just past Clappison’s

Corners on Highway 6, near Parkside Drive. Four white metal crosses

stand in a row, paint peeling and rust forming. A fifth cross stands

apart from the group. They mark the spot where a car crash just before

Christmas 2005, killed Vivian Porto, 43, her two children and niece, as

well as Robert Fox, 40, of Cambridge, who died of his injuries a few

weeks later.

Or the more unconventional memorial in the

middle of the soccer field of the West 5th campus of St. Joseph’s. From

afar, it appears a mound of weeds amid the expanse of a neatly mowed

lawn. Up close, there is a stalk of corn, small pink flowers, a broken

candle jar and some stones. There are no photos or names, but

presumably, this spot is meant to mark the spot where Michael Brewer,

30, was killed earlier this summer.

And then there are the flowers and photos

fastened to a cement electrical pole with bright red duct tape at King

Street East and Gage Avenue. This is where Matthew Power, 21, was mowed

down by a car while crossing the street with his friend on Nov. 5, 2006.

There was even a temporary memorial tacked

to a road sign in the area of Annabelle Street and Chester Avenue on the

west Mountain for a dog that was killed by a car after it got loose

from its home.

While some question the place that memorials

have along roadways and highways, grief experts and bereaved friends

and family recognize the role that these memorials play in the healing

process.

“We are being drawn there somehow,”

explained Abdolalian. “We feel obligated; we feel the need to be

connected; to be close to our loved one; to express our connection to

our loved one; to tell our loved one that we are always there for him,

that we’ll never forget him.”

Dr. Darcy Harris is the co-ordinator of the

thanatology program at King’s University College at Western University

in London, Ont. and has her own practice where she works with patients

dealing with loss and grief. She says many of her patients who have

experienced a traumatic loss gravitate to the accident sites where their

loved ones died.

“A lot of times, they weren’t there and they

feel a sense of guilt for not being there,” Harris said. “They weren’t

there to hold the person or to be there to comfort them while they were

dying. They wonder what their last breaths were like. It’s a very

difficult thing for them to try and resolve in their minds.”

Harris says roadside memorials are a way for

grieving friends and family members to do something meaningful in the

wake of something that feels meaningless.

“It’s a way of attaching significance and

meaning when they feel very helpless and powerless,” she said, adding it

is also a much more personal experience.

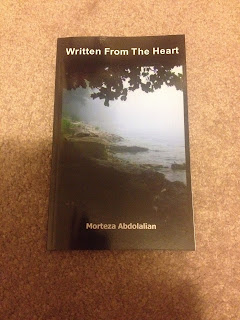

Abdolalian’s need to express his connection

to his son has extended beyond the flowers and remembrances left behind

on a pole at the intersection of James and Charlton.

He has set up a

blogin his son’s memory that’s designed to shine a light on the young man’s life while raising awareness for pedestrian safety.

“He was so young and you can’t forget. I can’t forget. It will be always with me.”

At the intersection of Upper Ottawa and

Fennell Avenue, there is a poster-sized photo of Paul James DaSilva

surrounded by weathered silk flowers. On it are the words, “very loved,

madly missed.” The 20-year-old died after he was stabbed outside of a

bar on April 10, 2009.

DaSilva’s mother, Shelley DaSilva, says she

normally avoids the place where her son was killed — “that corner is my

hell” — but makes the painful trip to maintain the memorial in her son’s

honour.

“I don’t want my son to be remembered as the

first homicide of 2009,” she explains. “He is Paul DaSilva. He is

somebody special. People are going to remember his face.”

In the past, she says, his memorial has been

torn down and trashed, but it’s been rebuilt and maintained, not just

by her and his friends and family, but by the community at large — and

for that she is thankful.

Harris says finding a memorial taken down or

moved provokes a “real sense of violation for a lot of people.”

“If it’s not causing a public nuisance, just

let it be,” she said. “And maybe it’s a reminder to all of us that

grief is really part of being human, and why are we so bothered when

someone chooses to honour grief in this way?”

905-526-3254 | @PattieatTheSpec